If you still find it hard not to stare at yourself when you’re on a video call, then you are not alone. Nor should you worry that this betrays a distressing level of narcissism. The author Nancy Mitford once observed that people who look at themselves in every reflection often do so not from vanity but a feeling that all is not quite as it should be. Video calls, which subtly distort our faces, are the perfect demonstration.

The speed with which we have folded video meetings into our lives is remarkable. In 2019, California video conferencing company Zoom had 10mn daily users. It now has about 300mn. Rapid uptake has resulted in new etiquette — the smile and silent wave that marks the end of a call, for example. But the level of self-surveillance that is required remains strange. This is why companies such as Microsoft, Google and Zoom have been quietly changing your appearance.

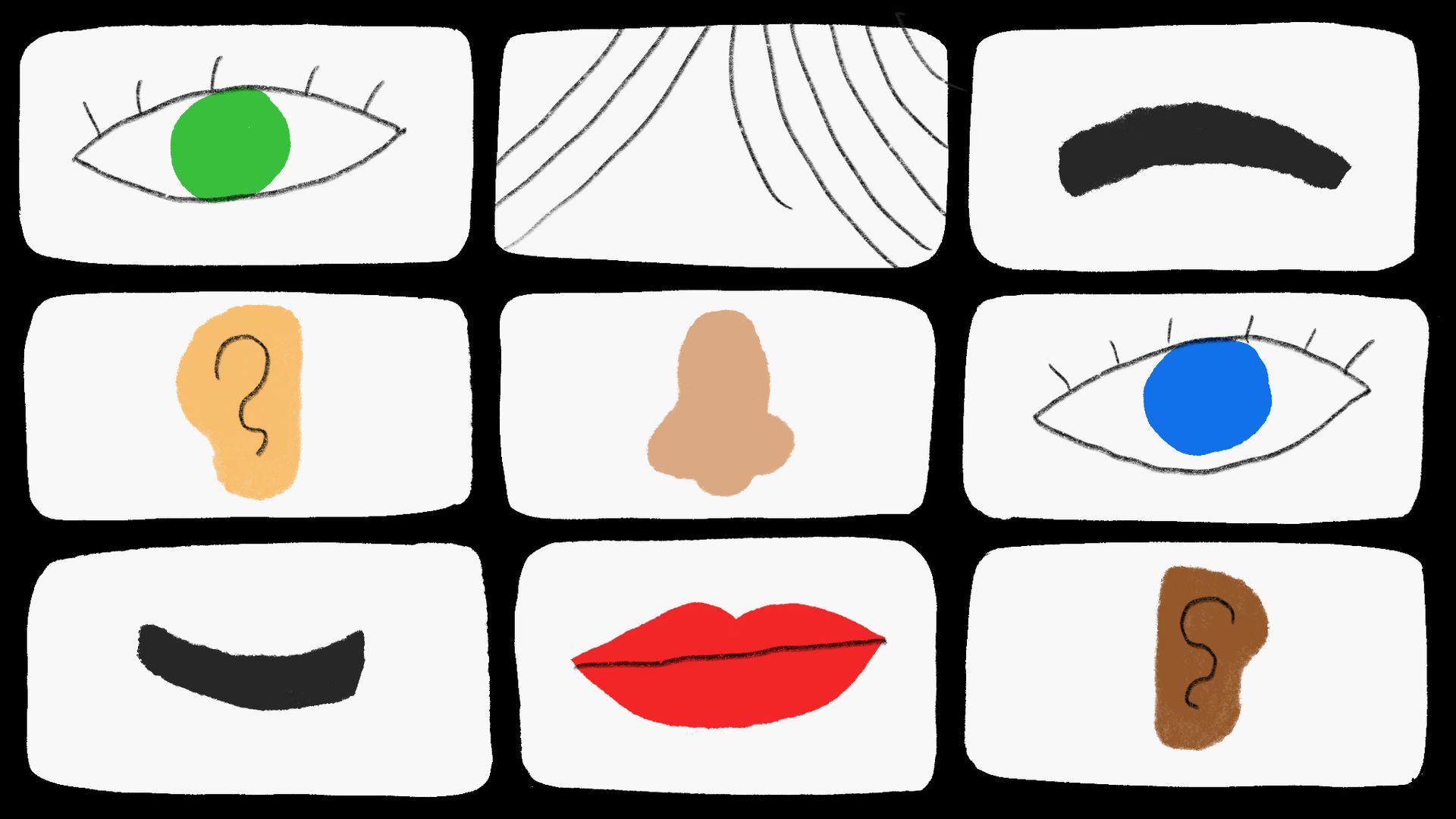

Last year, Microsoft introduced an eye-catching feature that allowed videocall users to pick from 12 digital make-up “looks”. The effects, created in tandem with cosmetics brand Maybelline, make cheeks appear rosier and eyes brighter. There is always the risk that a slow internet connection will produce a lag — move fast and your lipliner may not move with you — but it is a remedy to feeling drab in a morning meeting.

Adding digital make-up to something that is primarily a work tool had a mixed response from users. Why, asked one, was Microsoft fiddling about with appearances when other features were still lacking? “There’s still no way for me to create a single Teams channel meeting in the Teams Calendar app,” they wrote. “ . . . but I can put on lipstick? How is this a priority?”

In fact, how people look online is a priority for tech companies such as Microsoft. If that is someone’s main source of unease, then fixing it will help to ensure they keep using video conferencing platforms.

Perhaps you think you haven’t participated in this trend? If so, you’d be wrong. Not every change has been as dramatic as Microsoft’s make-up looks. Most are subtle and take place without your knowledge.

Take mirror view, which means that the screen you now see in most video conferences shows the version of your face that you see in a mirror — ie the one that you are most familiar with. Looking at the other version, the one everyone else sees when they look at you, tends to be jarring. Any asymmetry seems to be the wrong way round and so stands out. It’s something that smartphone makers and selfie-focused social networking company Snap figured out a long time ago.

Other tweaks include lighting effects and skin smoothing. Zoom says that it was the first to offer “touch up my appearance” filters. In 2022, Microsoft introduced a soft-focus filter. A year later, Google added what it called “portrait touch-up”.

Blame computers rather than your face for these fixes. PCs and laptops tend to have small camera lenses and record users relatively close up. That distorts appearances. Prominent parts of the face stand out more. Eyes can look smaller.

Seeing this slightly unusual, and unflattering, version of yourself may be behind the phenomenon dubbed Zoom dysmorphia, in which people fixate on the supposed flaws they see on screen. I asked a Bay Area cosmetic nurse if it was true that video meetings had led to a rise in customers seeking fillers, Botox and other invasive procedures. Not only had the numbers increased, she said, but some patients came to see her with screenshots of themselves from online meetings. This is backed up by a 2021 survey of US dermatologists who said most of their patients mentioned video calls as one of the reasons for pursuing cosmetic treatment.

Of course, the simple answer is to stop looking at yourself — or turn off self-view and concentrate on everyone else. But despite the complaints about how uncomfortable it is to be confronted with your own face for hours on end, this is a relatively unpopular option. A journalist at online magazine Wired suggested that hiding your image might induce a feeling that you have “dissolved into the ether”. I think it may be more to do with a mood-lowering suspicion that you need to monitor yourself in case your face does something weird in the meeting.

There is a final, rather drastic, remedy. Google’s AI model Gemini is planning a new feature called “Attend for me” in which it will turn up to a video meeting on your behalf, deliver your message and then send you a recap of the other attendees responses. It sounds fantastically impolite and the sort of feature that will lead to no one attending video meetings in person ever again. For those who dislike looking at themselves online, that would be the dream scenario.