Wander around Port Sunlight, Bournville, or Saltaire, and the genuine concern of their founders for the wellbeing of the workers is manifest in the fabric of these British model towns developed by enlightened entrepreneurs, even if it is at times oppressively paternalistic. Other company towns, like those depicted in Depression-era novels, were simply exploitative, paying workers meagre amounts in company money that could only be spent at costly company stores.

This was the comparison that came to my mind when reading Markets and Power in Digital Capitalism by Philipp Staab. The book explores what is distinctive about today’s digital capitalist economies, focusing on the extensive reach and power of the Big Tech companies, and looks back in time to find apt comparisons. Yet, rather than look to the 19th century luminaries — the Lever brothers, the Cadbury family or the mill baron Titus Salt — who developed those model towns, Staab, professor of sociology at Berlin’s Humboldt University, offers a different, earlier parallel, namely the colonising businesses of the age of empire, such as the East India Company.

Big Tech firms operate a corporate monopoly with government blessing, a “privatised mercantilism” operating through “proprietary markets”. This comparison suggests the digital capitalist economy is inherently exploitative. But the book is more nuanced — and therefore more interesting: it is not just another anti-capitalist rant.

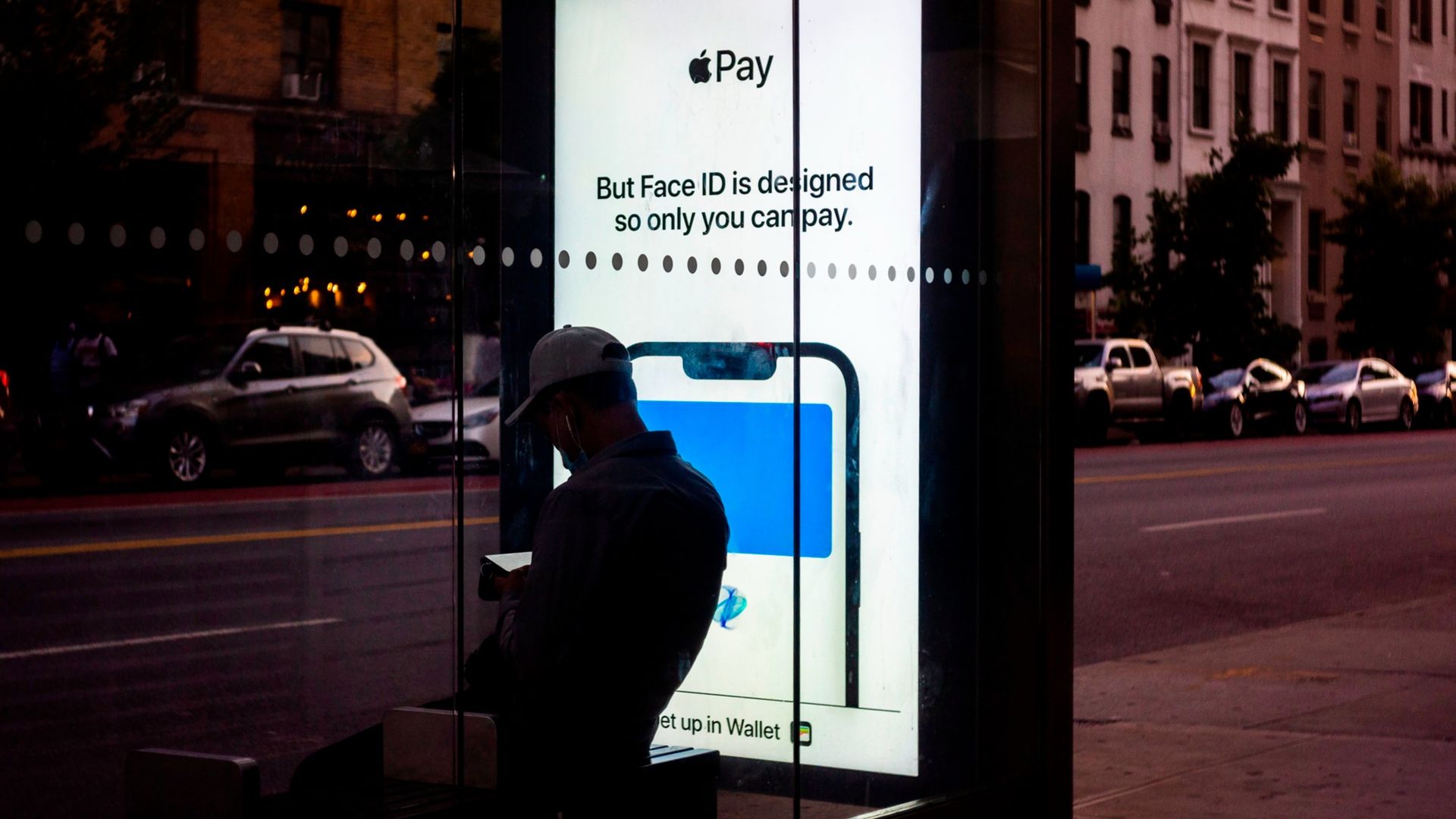

For, as Staab admits, and as the evidence indicates, the billions of users of digital technologies greatly value the (often free) services they get. Few people would disagree about the negative aspects of Big Tech, including their immense power, but it undermines the credibility of some of the critics to ignore the positive aspects entirely. The combination of valued amenities with the exercise of control is what makes Big Tech’s walled gardens — such as the provision by the likes of Google or Apple of a world of operating systems, internet search, email, payment services, maps and so on — as reminiscent of company towns as of the East India Company. Apple’s locking in consumers and locking out other providers is at the heart of the new Department of Justice anti-trust case against the tech giant.

Given this mix of good and bad, Staab makes several interesting observations. One of the main weapons being deployed against Big Tech is competition policy, intended to limit or roll back their market power. But as Staab says, these are not like normal markets: “They are not primarily producers operating in markets but markets in which producers operate.”

In other words, the digital platforms have become the field on which many producers in the economy themselves innovate and compete. Big Tech firms have expanded their areas of operation from an initial offer (bookselling for Amazon, making computers for Apple, and so on) to provide an ever-increasing range of services. They are increasingly building their own infrastructure of data centres and undersea cables. Their ambition is that both sides of the market, producers and consumers, find everything they might need as an economic agent within the walls — the information, the means of payment, the fulfilment. The individual’s chosen Big Tech can provide their income, while filling their leisure and consumption time too — and making it ever-harder to leave.

As Staab notes, this all-embracing approach has also brought the digital economy’s potential for innovation and entrepreneurship inside the walled gardens as the only way a start-up can grow is by being acquired by Big Tech. One little-noticed implication is that competition policy might in fact torpedo this dynamic, as the US, EU and UK authorities have all recently prevented acquisitions that might previously have been nodded through.

An example is Amazon’s recent decision to drop its bid for iRobot, maker of the Roomba vacuum cleaner, in the face of likely EU and US vetoes. Old-style competition thinking would not have seen domestic cleaning robots as being in the same market as online retail and cloud computing. New-style competition policy sees that this has allowed digital companies to build massive market power and aims to stop such acquisitions. If extended, this tougher enforcement could end the get-rich quick exit strategy of the start-ups.

Other concepts in the book seem less useful. In particular, Staab argues that the economy is characterised by “superabundance” and saturated demand, so that the platforms need to profit by making it too hard for users to switch. He seems to believe everybody had everything they could need by the 1970s, which is not how I remember that decade. The fact that “sales suffered” in the early 1970s is surely more easily explained by macroeconomic events than the senescence of the previous capitalist system of accumulation. Still, for all that the book is mainly in conversation with other critics of capitalism, it is jargon-free, well-argued, and thought-provoking.

Markets and Power in Digital Capitalism By Philipp Staab Manchester University Press, £20, 184 pages

Diane Coyle is professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge