Corporate Turkey is finally feeling the pinch of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s radical departure from years of unconventional economic policies. Not everyone is happy with the new normal.

Erdoğan, who once called high interest rates the “mother and father of all evil”, made the kind of volte-face after his re-election in May 2023 that seemed almost unimaginable to many Turkey watchers. He started by tapping Mehmet Şimşek, a highly-regarded former deputy prime minister and City of London bond strategist, as finance minister.

Şimşek inherited a $1tn economy on the brink. Years of ultra-low interest rates fuelled runaway inflation, while a burst of pre-election stimulus — including a month of free gas for households and minimum wage rises — ignited furious demand for imports. Economists were concerned that Turkey was very close to a balance of payments crisis before Şimşek was appointed in June 2023.

Şimşek wasted little time in vowing to reinstate “rational” economic policymaking and reshuffling the management of Turkey’s central bank. Erdoğan went so far as publicly vowing that “tight monetary policy” would be the tool for fighting inflation, an extraordinary reversal from his years-long insistence that low rates cure rather than cause rapid price growth.

The central bank, which is now run by former US Federal Reserve economist Fatih Karahan, has lifted its main interest rate from 8.5 per cent last June to 50 per cent in March. The mechanism for the transmission of monetary policy to the economy that was severed by the previous unorthodox measures appears now to be more functional, meaning once-easy financial conditions are tightening.

“The business world has transitioned from a period of abundant cash with low interest rates but limited access to credit to a period of scarce cash and high loan interest rates, with even more limited access to credit,” said Süleyman Sönmez, president of the Turkish Business Confederation.

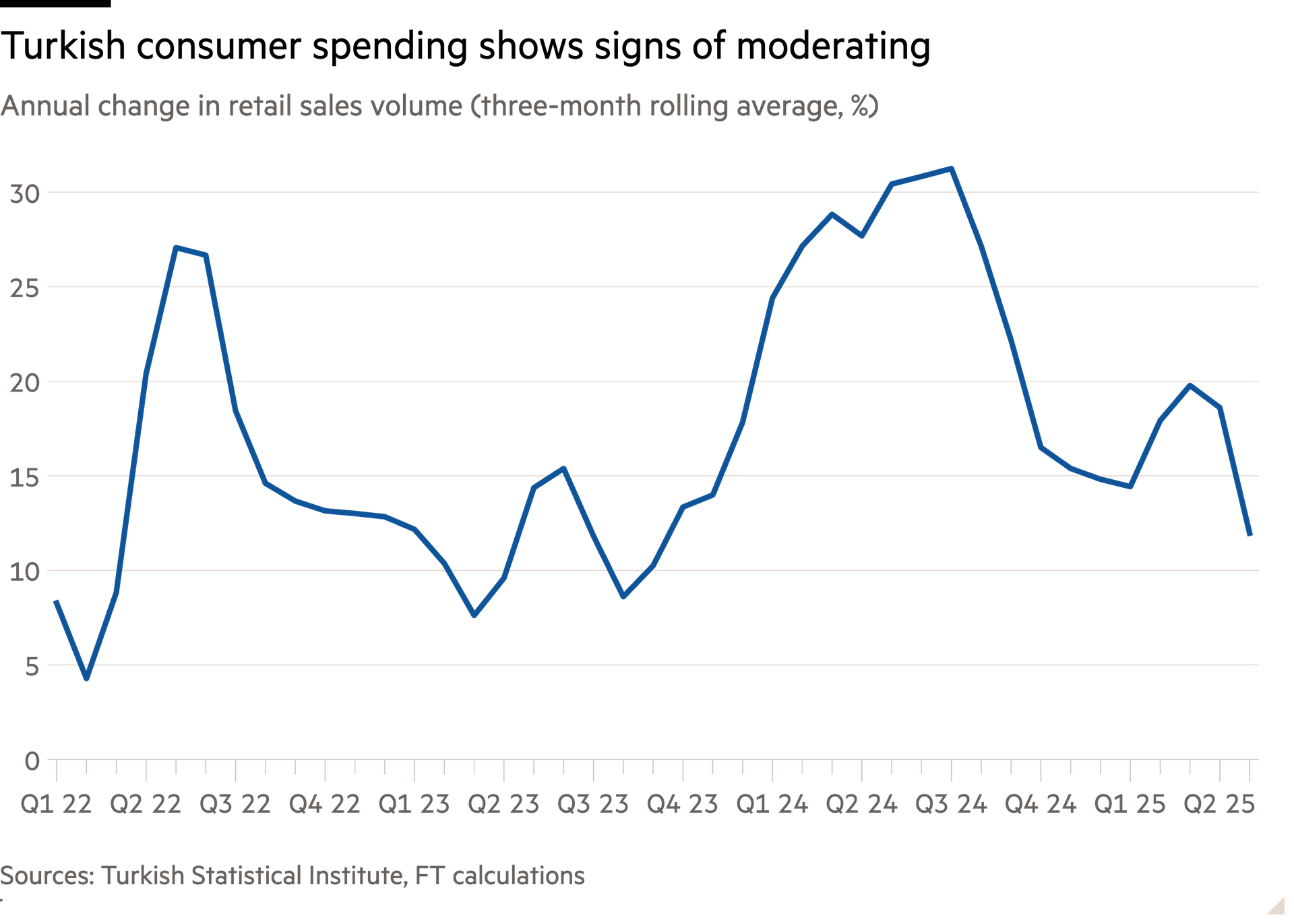

Consumer demand has remained robust, helped by the lingering effects of last year’s pre-election giveaways and because household debt levels remain low compared with other emerging markets. Such demand was one reason why many businesses were surprisingly sanguine about the inflation rate, which peaked above 85 per cent in late 2022 before cooling to 72 per cent last month. Exporters also were boosted by a 33 per cent decline in the real exchange rate, a measure of the competitiveness of Turkish goods, from the start of 2018 and May 2023.

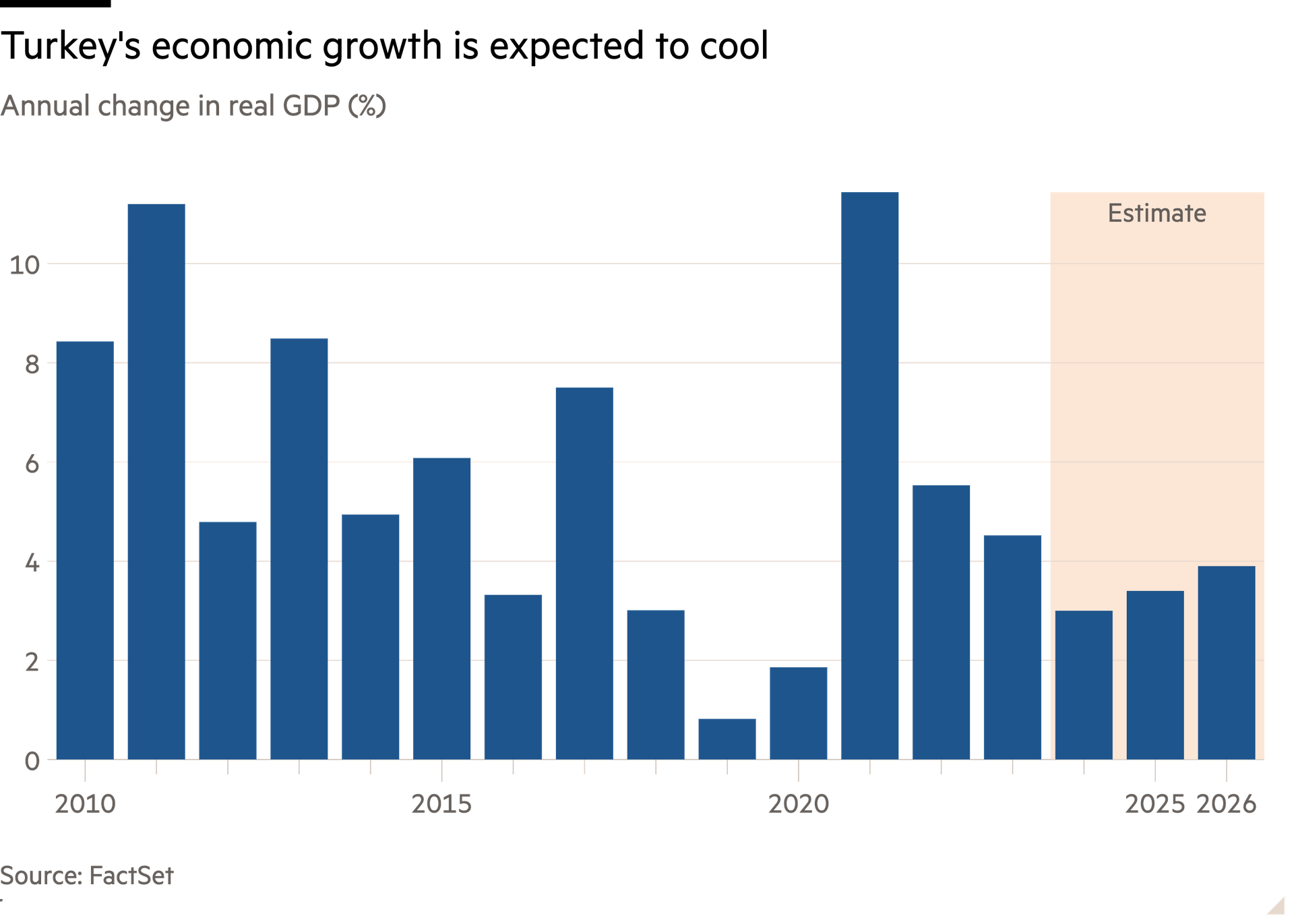

Still, once red-hot growth in consumption is cooling, and economists expect a further slowdown after policymakers refrained from a mid-year minimum wage rise. Şimşek is trying to engineer a soft landing: economists polled by FactSet expect inflation-adjusted output to grow 3 per cent this year, compared with an average rate of 5.2 per cent in the decade to 2023. This modest deceleration still represents a seismic shift for some companies.

Businesses have broadly backed Şimşek: “We recognise that the slowdown in growth is an integral part of the disinflation process,” said Sönmez. But behind the scenes, there is a growing sense of discontent in some corners of the business community. One former top economic official notes that more than a year into the policy shift, inflation is still far from stable and many companies are stuck in a “wait-and-see mode”, making it difficult to make long-term decisions.

The ex-official said that there was also a feeling in the business community that Şimşek’s messaging had been too heavily focused on wooing international investors, who are now wading back into the Turkish lira and the domestic debt market that they had shunned for years. He added that many businesses had expected conditions to have started easing as soon as this summer and are beginning to run out of patience.

Exporters have also grown increasingly frustrated at the 20 per cent rise in the real effective exchange rate over the past year. “Turkey is at least 40 per cent more expensive than its competitors in terms of dollar-based pricing. As a result, Turkey is losing its competitiveness,” said Mustafa Gültepe, head of the Turkish Exporters Assembly, at a recent press conference. Lenders are also bracing themselves for a potential rise in non-performing retail loans as conditions tighten, according to one senior Turkish banker.

Karahan has made a repeated vow to do “whatever it takes” to fight inflation. If price rises do not start to slow, businesses might need to prepare for a prolonged period of tight policy that eventually damps demand.