The US economy has done far better over the past few years than many would have expected, particularly given the multiple headwinds from the pandemic, US-China decoupling, the war in Ukraine and general political chaos in Washington.

The country has enjoyed an almost immaculate economic cooling, along with a still-robust jobs market and good overall gross domestic product growth. Particularly when compared with other countries, the US economy looks as good as it could be right now. However, there is one conspicuous fly in the ointment — housing.

You can see it in last week’s consumer price index numbers, which showed inflation to be a bit higher than was forecast. The main culprit, aside from ever-volatile food and oil prices, was housing. The shelter index portion of the CPI was up 7.2 per cent over the past year, accounting for more than 70 per cent of the total increase in all items, aside from food and fuel.

The inflation numbers raise the prospect of another Federal Reserve interest rate increase in the future, at a time when Wall Street was betting that hikes were over.

But would that be the best policy solution for the housing problem in the US? There’s a strong argument to be made that the answer is no. For some time now, the core inflation story in America has been all about housing. Unlike other markets, including the UK, where prices have dropped 13.4 per cent in real terms from their March 2022 peak, the American housing market is not cooling, despite multiple interest rate hikes.

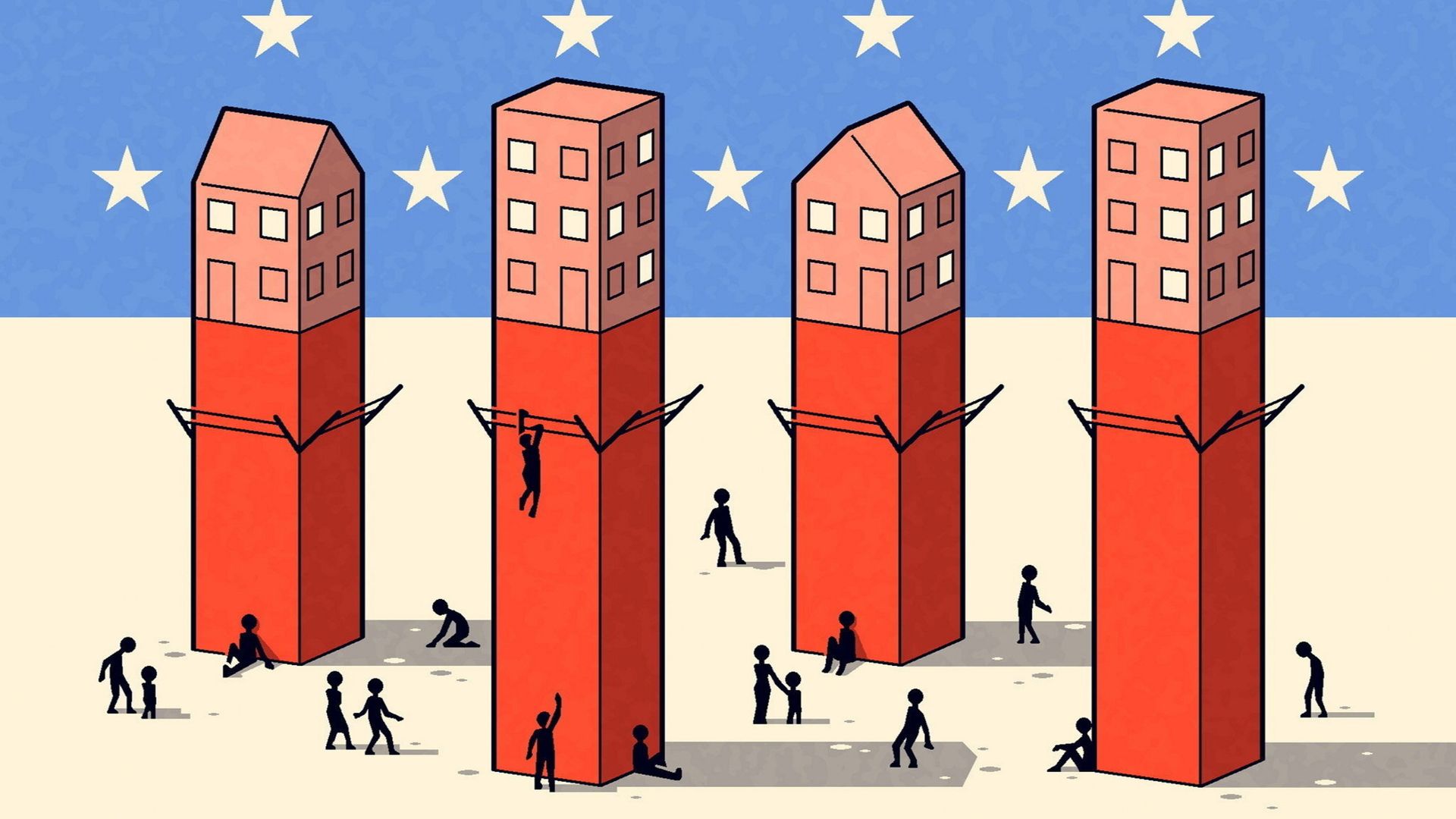

Indeed, you can argue that rate rises have made things worse in housing markets. How is this to be explained? Start with the fundamental problem, which is too little housing supply relative to demand in the US. The country’s housing production hasn’t kept pace with household formation since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, when the number of housing unit starts dropped off a cliff. Since then, demand has far outpaced supply, leaving the US millions of units short of what its population needs.

Part of this is about nimbyism, meaning the “not in my backyard” approach to housing policy at a local level. While plenty of Americans in big cities such as New York, Los Angeles or San Francisco would agree that there’s a need for more affordable housing, and indeed more housing in general, few prosperous homeowners (or even renters) would vote to locate such a project near them.

Studies have found that city politics around zoning tends to favour the opponents of plans rather than the developers. This is a key reason that housing remains constrained.

This problem is being further fuelled by an influx of migrants to sanctuary cities in the US, where shelter is in theory guaranteed but in practice is not available. There are also lingering issues with inflation on materials and labour since the pandemic. These have either deterred new home construction or simply made it unaffordable.

Housing is, in many ways, America’s last remaining supply chain problem. Fuel prices are up, as well, though that issue will eventually be resolved as US wells pump more and Opec adjusts supply. But the problem of housing inflation, which has been unwittingly exacerbated by the Fed, won’t go away any time soon. The home price/mortgage rate arbitrage is working against homeowner mobility.

The current 30-year fixed mortgage rate in the US is around 8 per cent. That’s up from under 3 per cent in 2021. Meanwhile, the median house price is up 29 per cent, from $322,000 in 2020 to $416,000 today. Add to this the fact that many homeowners locked in very, very low rates over the past few years. Unless you are about to see your rate reset, it’s extremely hard to justify moving.

My husband and I, for example, have a variable rate of 2.875 per cent that won’t be reset till 2031. With my second child about to leave for college next year, I would love to downsize from the family home and move in to something smaller. But the combination of a still frothy housing market, coupled with high mortgage rates and the overall tax burden associated with home sales in places such as New York, means that it doesn’t make financial sense for us to leave — we would pay more for much less.

This is the dynamic that is keeping prices high, even in the face of higher rates. And it’s a recipe for continued inflation, particularly if rates continue to rise.

Some economists are now calling on the Fed to rethink its traditional approach based on this confluence of factors. “I have moved from scratching my head, to being annoyed, to frankly being livid at central banker devotion to cyclical models that simply don’t apply to the post-pandemic era,” says Dan Alpert, managing partner of Westwood Capital. Alpert is a professor at Cornell Law School who has long advocated that the Fed should think more creatively about housing market inflation when considering new rate rises.

If the current paradigm of high prices, high rates and insufficient supply continues, something will have to give. We may not see a major housing market correction in the US soon, given how many people are locked into low rates, but unless a lot more homes are built in the next few years, it will be very difficult to manage America’s housing affordability crisis.